Nothing Holds On Its Own: social architecture and how we all live together

By Alastair JR Ball

The air inside Nothing Holds On Its Own feels charged, not with spectacle, but with proximity. You sense it before you name it: the press of breath, the small, accidental symmetries between strangers, the hush that falls when a performance begins and you realise, with an odd tenderness, that you are part of the work simply by being there.

Green Grammar’s latest exhibition is less a show than an experiment in being-with, a curatorial attempt to trace what Marguerite Duras once called “the web of our existence,” where nothing, and no one, ever stands alone.

In a cultural moment obsessed with individuality, the personal brand, the solo genius, the algorithmic feed tailored to your exquisite uniqueness, Nothing Holds On Its Own feels almost insurgent. It insists that we are porous, symbiotic, and reliant. That love, care, and attention are not private emotions but social architectures, invisible yet load-bearing.

Wider ecology of connections

The exhibition takes Duras’s La Vie matérielle as its touchstone, but where Duras found poetry in domestic entanglement, Green Grammar extends her logic into the wider ecology of connection: between people, materials, memories, and the ghosts of the digital age.

The gallery itself, a minimalist open space in the brutalist shadow of Metro Central Heights in Elfant and Castle, becomes a testing ground for intimacy. The curators, Moyu Yang and Chang Wang, who together are Green Grammar, have gathered a constellation of artists from across cultures and generations, creating a dialogue that feels less like a hierarchy than a gathering.

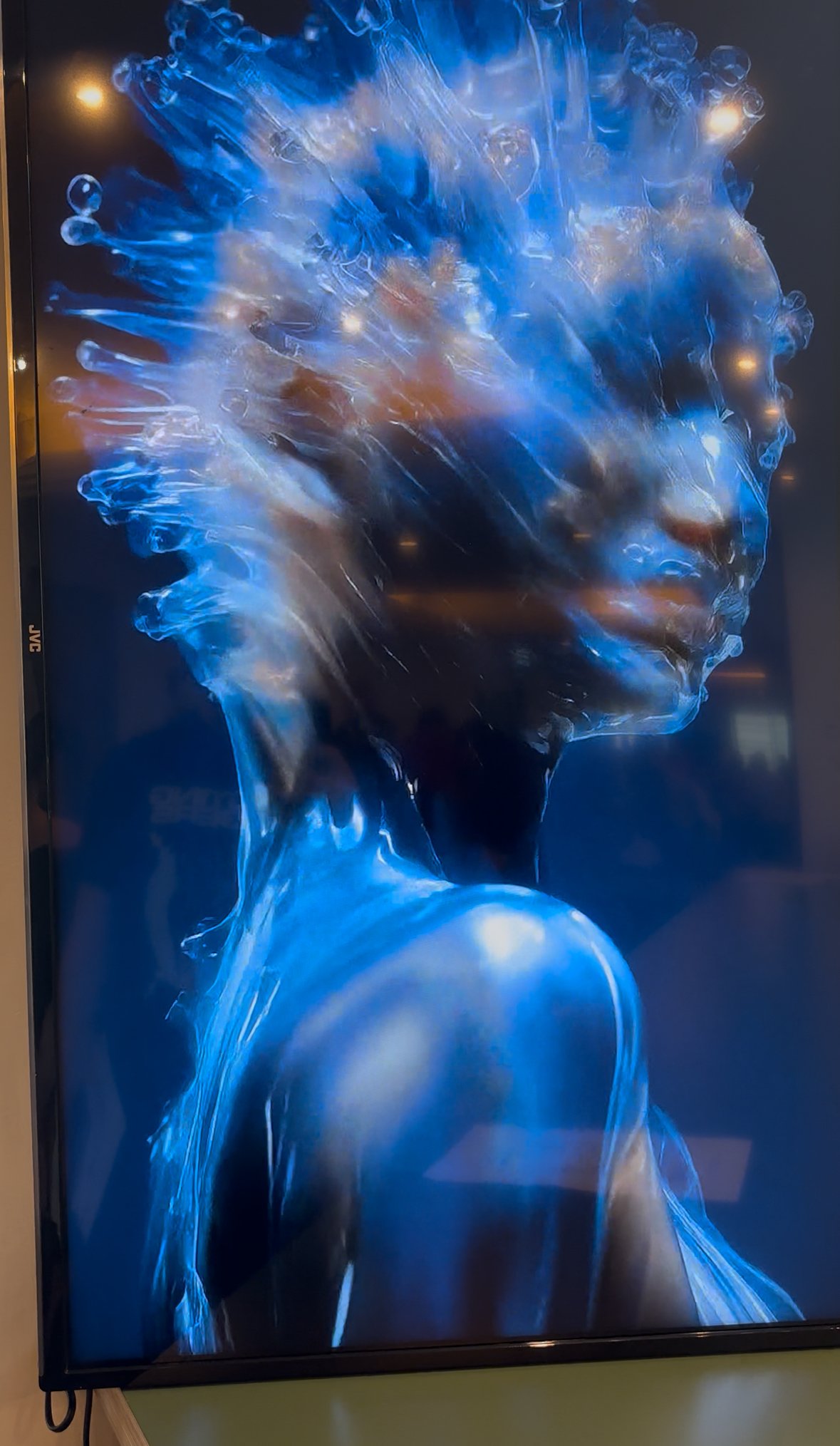

One of the most quietly devastating works is by Xinyuan Yan. In a darkened corner, she projects faint, pixelated images of her late grandmother, found, hauntingly, on the Chinese equivalent of Google Maps, onto the gallery wall. The images flicker between domestic banality and spectral revelation: a woman caught mid-step, frozen forever in algorithmic purgatory.

Between love and surveillance

It’s a work that sits between love and surveillance, grief and data. In an era when every loss is archived, Yan’s gesture asks what remains of intimacy once it’s been mediated by the machine. And yet, watching the audience gather, whispering softly to one another, it became clear that the projection had done something extraordinary: it had summoned a collective act of remembrance.

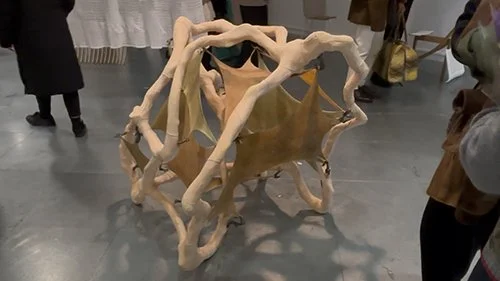

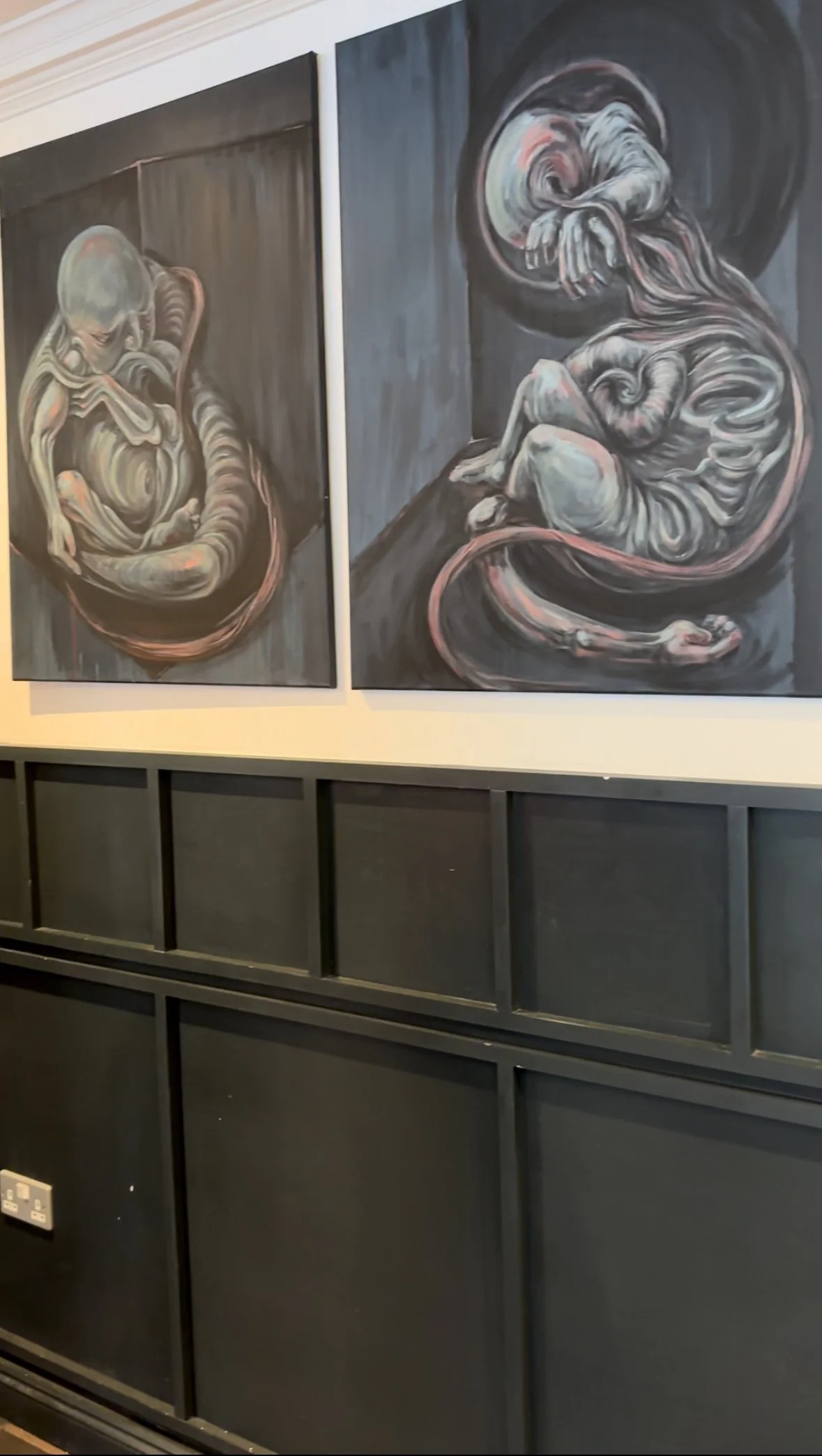

Nearby, Georgia Salmond’s sculptures anchor the exhibition in something bodily. A London-based artist known for her mould-making and life-casting, Salmond’s practice sits squarely within the uncanny. Her work here included masks of faces separate from bodies, gazing up from the floor with empty eyes.

At first glance, they resemble death masks from an ancient grave; look closer and the seams, pores, and air bubbles betray their contemporary origins. They are eerie but tender: a taxonomy of touch that collapses the distance between maker and made. In Salmond’s hands, the psychoanalytic becomes social. The unconscious, it turns out, has fingerprints.

Like the Great River

Then there’s the story that seemed to ripple through the opening night: the retired farmer from rural China, discovered by the curators after her daughter-in-law posted her embroidery online. Unable to read or write, she began “drawing” with thread after moving to the city, using discarded fabric to recreate the valley where she was born.

Her piece, Like the Great River, is a meditation on displacement and resilience, art made not for recognition, but survival. Standing before it, surrounded by Londoners from every conceivable background, you could feel the word “authentic” reclaiming its meaning. Not as an aesthetic category, but as an act of truth-telling.

What makes Nothing Holds On Its Own remarkable isn’t simply its sincerity, but its refusal to separate the art from the atmosphere. During Kairi Tokoro’s performance, a fluid musical composition played on the artist’s object-sculpture, I looked around the room and saw a diverse group of people all captivated, united in a mutual love of art.

Communal presence

This sense of communal presence runs throughout Green Grammar’s curatorial ethos. It’s the latest iteration of their ongoing interest in human connection, roots and our environment. It’s not a sterile, theory-heavy, contemporary art exhibition, but in a deeply personal, embodied.

They understand love not as muse but as methodology. For them, curating is a form of care work: connecting artists across continents, creating spaces where vulnerability is shared rather than performed.

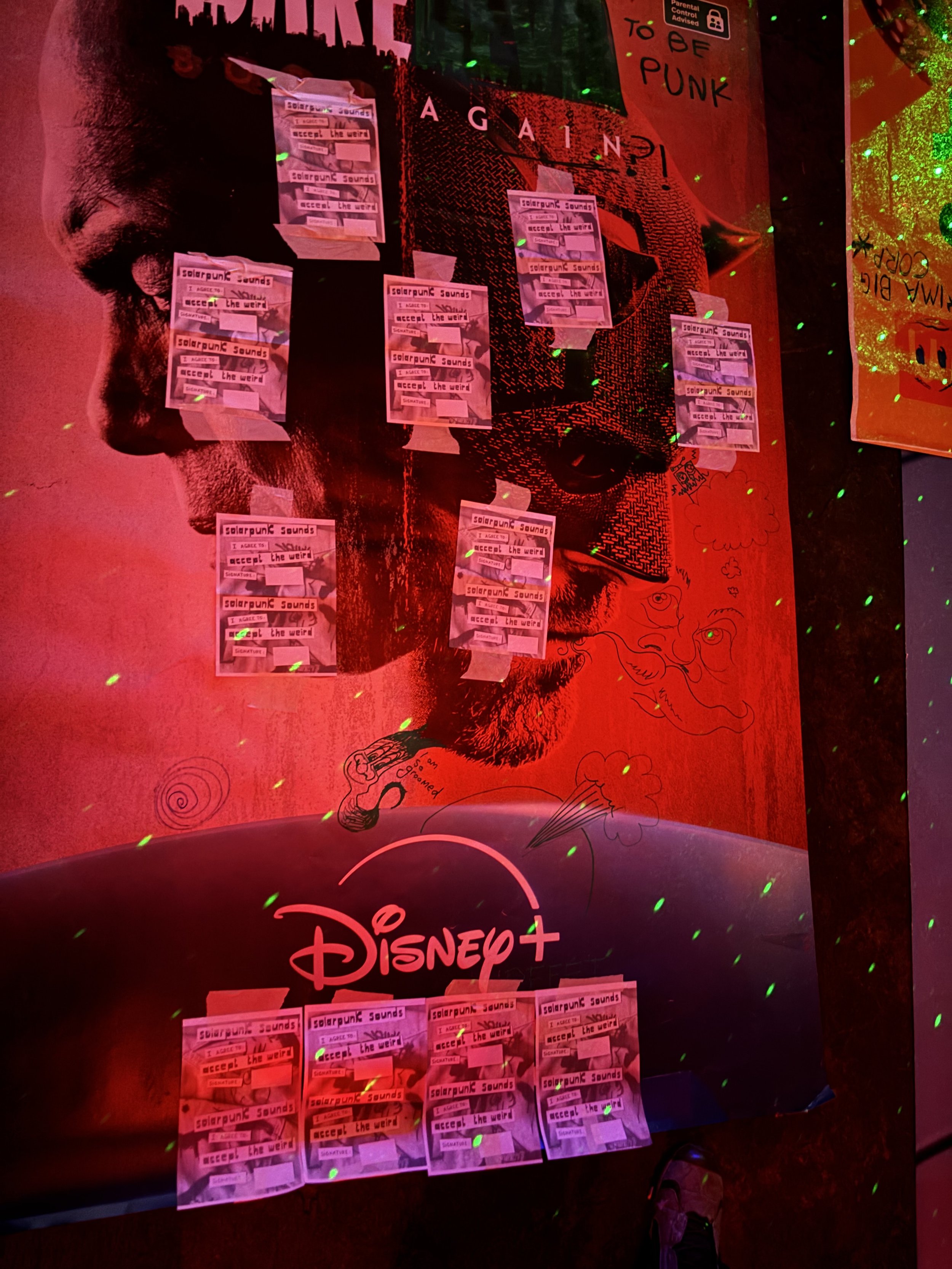

At a time when so much contemporary art is preoccupied with irony or market logic, Nothing Holds On Its Own risks sincerity, and in doing so, feels radical. It argues that art’s most urgent function is not to innovate or provoke, but to remind us that we exist through one another. That in the midst of ecological collapse, political polarisation, and digital alienation, interdependence is not weakness but survival.

Loves becomes infrastructure

Leaving the Annex that evening, I found myself lingering at the threshold, watching as people hugged, exchanged numbers, and promised to meet again. The exhibition had done what few manage: it had made art feel like a form of collective respiration.

Love, in all its awkward, improvised forms, had become infrastructure once more. And for a moment, in that shared exhale, the city itself felt less lonely.