Dancing on Advertisements

By Alastair JR Ball

I remember walking through Tottenham last winter, skint and raw-nerves, watching the world get brighter and louder with adverts I couldn’t afford to believe in. New iPhones, luxury toothpaste, craft beer at £8 a pint. All of it screaming in HD colour across walls, windows, and screens, promising salvation, if I just bought the right thing. I was meant to be grateful for these offers, but instead I felt like I was being hunted.

Nothing about their version of life made sense to me. I didn’t want it. I didn’t want to optimise, lose weight, or pretend I was living my best life on Instagram.

The graffiti, still visible down side streets off Tottenham High Road, once a symbol of resistance, felt neutered too. Stripped of teeth and commodified; if the zeal with which a Banksy was removed from the wall of a Wood Green Poundland is anything to go by. Most likely it’s in a private art collection now or is hanging in a Mayfair art gallery, framed and flogged to property developers as “urban aesthetic.”

Liberation in the form of a sharpie

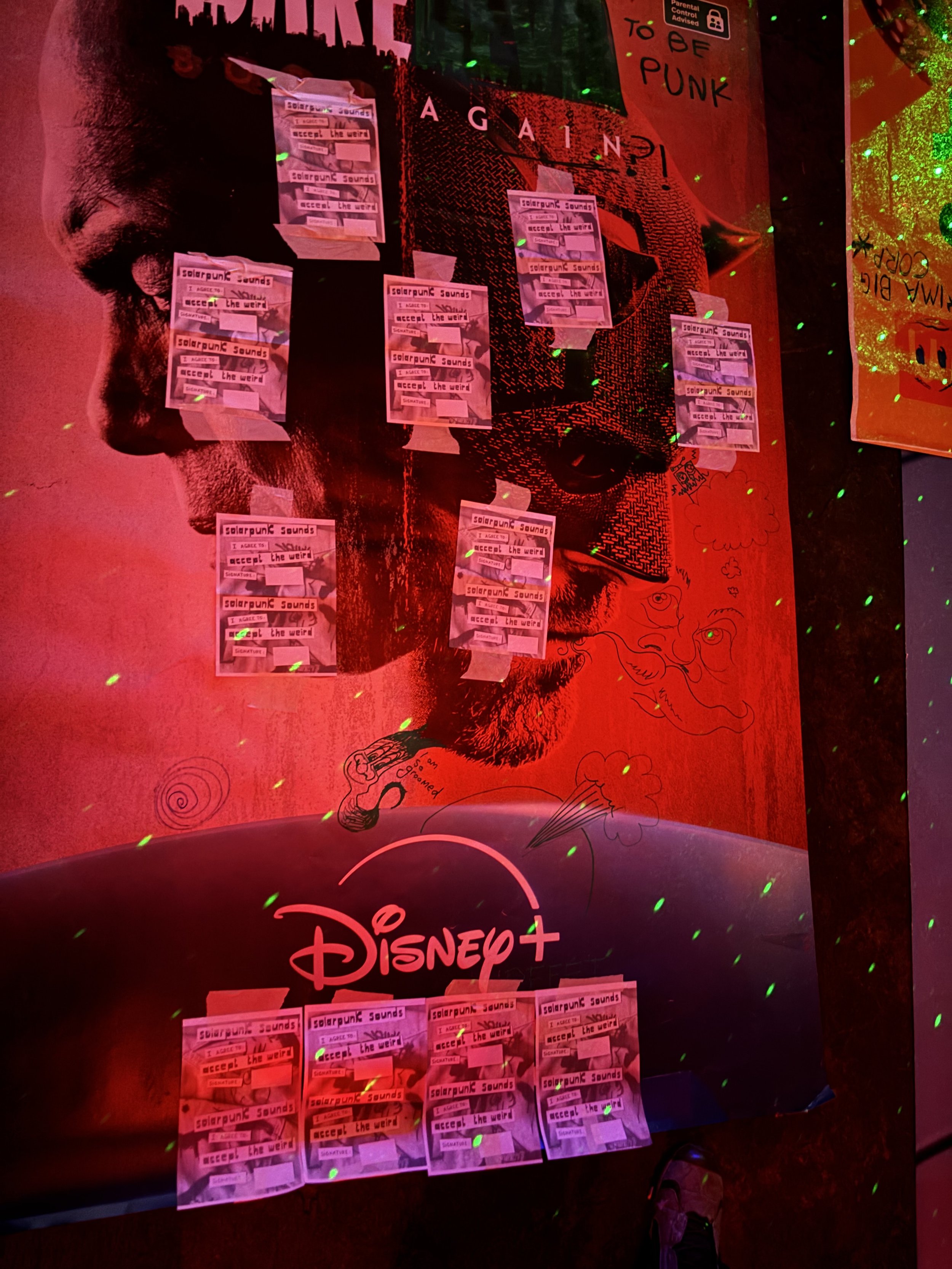

That’s when I found Solarpunk Social at The Post Bar, where I was handed a sharpie and some plants, then shown adverts freshly liberated from the glass of a London bus stop. It was joyful. It was political theatre. It was exactly what I needed.

Graffiti and subvertising are usually dismissed as vandalism. Even the more generous critics relegate them to “street art,” as if the spray can is somehow inferior to the oil brush. Or it’s only praised when it becomes worth a huge amount of money, like the Banksy liberated from a Poundland Wall to generate profit for someone somewhere.

What if, instead of seeing graffiti as a static image, we saw it as performance? What if the street isn’t just a gallery, but a stage, and every sprayed line, every hacked billboard, a fleeting act in a radical theatre of resistance? That’s the possibility that subvertising offers.

Defacing as a political gesture

Subvertising, short for “subversive advertising”, is the street’s remix culture. Think of it as cultural detournement: Nike slogans reworded to critique sweatshops, oil companies’ greenwashing torn apart with biting counter-texts, McDonald’s golden arches twisted into protest symbols. It’s an art of interruption, of jamming the signal.

Unlike sanctioned murals or publicly funded street art festivals, subvertising is deliberately illegal, unauthorised, and often anonymous. Its power lies in what it interrupts: the endless stream of ads that tell us who we should be, what we should buy, and how we should feel about our lack of it.

It’s the art of culture jamming: turning “Have it Your Way” into “Have Nothing, Be Grateful.” It’s resistance in Helvetica Bold.

Billboards lie. Spray paint doesn’t

Graffiti and subvertising reclaim the visual commons. They’re not just images, they’re insurgencies. Every tag is a refusal. Every defaced billboard is a vote of no confidence in the capitalism of the eye. These are performed critiques: urgent, embodied, and defiant.

Commercial messages are everywhere. We don’t consent to them. We don’t vote for them. Yet they haunt our commutes, leer at us from bus shelters, shout at us from phone screens. Subvertising answers back.

The graffiti artist as performer

Subvertising doesn’t happen in studios. It’s born in shadows, alleys, train yards. It’s as much choreography as creativity, part ninja, part dancer. There’s the scouting, the route planning, the escape map. The timing is precise. The adrenaline is real. The risk is the point.

This is not unlike performance art. Marina Abramović may have stared for hours, but hanging off scaffolding at 3am with a police van circling by seems more daring and more confrontational.

Subvertising is graffiti’s punk sibling: angry, quick, uninvited. A visual insurrection. A performed critique. Not just the image, but the body involved in putting it there, climbing, sneaking, pasting, running. It is live art made in alleyways and scaffolded silence. No stage, no script, just a flash of intention before the cleaners come.

Witness and audience

That night at The Post Bar, I realised how much I’d been craving something physical. Something collective. Not just reading radical theory on the tube while the world burns, but being in the mess with other people. Holding hands. Laughing. Risking. Making something together and then stomping on it with muddy boots.

It reminded me of performance art, not the solemn chin-stroking kind, but the raw, sweaty kind. Joy as an act of resistance, like the Idles album said. The act itself was the message. The audience? Whoever had popped into The Post Bar that night, lured by craft beer and reggae provided by Street Light Sound System.

Then, when the adverts went back out into the world freshly remixed and placed back in their protective glass the audience became whoever clocked the weird collage above the McDonald’s ad and did a double take. The commuter. The bus driver. The stoned teenager, walking home at 3am. Like all the best art, it was fleeting. It might be gone tomorrow. That’s what makes it matter.

This is not for Sotheby’s

Unlike the rarefied hush of the gallery, subvertising’s audience is unpredictable. It’s the morning jogger, the night bus driver, the teenager on her phone at the zebra crossing. It’s the pigeon.

This is the street artist's great democratic risk and reward: anyone can see it, and anyone can ignore it. However, those who do see it? They become part of it. Reactions, laughter, disgust, Instagram posts, arrests, are all part of the artwork’s performance arc.

Like any good live act, subvertising’s lifespan is short. A wall might be buffed clean in an hour. A remixed ad placed back in a bus shelter may be taken down by the council before sunrise. Or it might go viral before disappearing. Subvertising lives, and dies, on borrowed time.

Dancing on advertisements

We didn’t do it alone. Solarpunk Social at The Post Bar and the London School of Solarpunk are full of people who think the future can still be beautiful. We know we need new myths, new dreams, and new ways of being together in the city. The Post Bar is one of the last places where this kind of thing can happen, where rebellion can be tender, queer, funny, and covered in biodegradable glue.

After we had remixed the adverts, they served as an impromptu dance floor as we bopped the night away to reggae and dub. The walls of bus stops had become our floor. This was an act of personal liberation. I had honestly never danced on an advert before that night.

The street is still a stage. It’s where graffiti brought down regimes during the Arab Spring. It’s where Black Lives Matter murals carved power into pavement. It’s where Brandalism turned Coke slogans into climate warnings. This isn’t art about politics. This is politics. Not in galleries, but in gutters. Not for sale, but for sharing.

The street as a site of resistance

Throughout history, graffiti has flourished in moments of upheaval. In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, walls bloomed with revolutionary stencils. In Minneapolis, George Floyd’s face became a muraled martyr. In London, Solarpunk Social do their part to stand up to the oppressive tide of late-stage capitalism.

These works of art are not decorative. They are declarative. They refuse commodification. They ask not to be bought, but to be felt.

Unlike most gallery art, they don’t whisper. They scream. They exist in defiance of permission. They resist the sanitised, privatised, corporatised aesthetics of urban life.

The message in the mess

They are art, yes, but they are also acts. At The Post Bar we weren't creating masterpieces. We were becoming art. Temporary, illegal, unforgettable.

Subvertising isn’t just a visual practice. It’s a temporal one. It happens. Then it vanishes. It leaves behind a question. Not just “what does it say?” but “who did it speak to? Who did it challenge?”

That night, we left The Post Bar giggling, tipsy, looking back at the adverts we’d re-written. There was glue on our hands and slogans under our boots. It was messy. It meant something.

Escaping the bland commercial world

I felt rejuvenated from connecting with people instead of doom scrolling past adverts. It was exciting to be part of an act of resistance to the bland commercial world that a few hours earlier had seemed inescapable.

Graffiti and subvertising are verbs. Things you do. Things that interrupt, provoke, delight. So next time you see a billboard, don’t just ask what it says. Ask who it’s speaking to. Ask who made it. Ask what it’s stealing from you, and how you might steal it back.

Maybe the truest art isn’t in a museum. Maybe it’s smeared across the side of a bus shelter, fading in the rain, daring you to dance on it.