If you looked up evil in the dictionary there would probably be a picture of Adolf Hitler or the Nazis, which is fair enough as they murdered over six million people. Many books have been written trying to understand the evil at the heart of the Nazi regime, but the definitive work was written by Hannah Arendt in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

The book chronicles the life and trial of Adolf Eichmann who, amongst other things, planned the transportation of Jews during the Holocaust that allowed for millions to be moved to camps where they were murdered. Eichmann was not remarkable for a cold calculating intelligence. He wasn’t evil like Hannibal Lecter or Darth Vader. He wasn’t possessed by a fanatical hatred of Jews, beyond the antisemitism that was prevalent at the time. Eichmann wasn’t remarkable at all, really, apart from the remarkably appalling deeds he was a part of.

Arendt wanted to explain how someone so normal could be a key part of such massive evil. Her book also explores how we got to the point where great acts of evil weren’t conducted on the battlefield or in the sacking of cities, but by bureaucrats behind desks. Her book remains the best and most insightful exploration of human evil, and should be read by everyone.

The work of genocide involves a lot of bureaucracy

Eichmann’s job was a senior - but not quite at the top - bureaucratic position in the public sector, but he participated in one of (if not THE) most awful things that has ever happened. Arendt’s book shows that in modern industrial society, the everyday work of genocide is like that of any other office job, and the people most suited to it are the same office drones that are found all over the world.

The book shows how a totalitarian system like Nazi Germany became a part of normal life. The Holocaust needed paperwork. When we think of evil, we think of something abhorrent or something whose every part is disgusting to us as moral human beings. We don’t think of things that are dull, like paperwork. Arendt argues that under totalitarianism, evil becomes everyday. It no longer looks like evil. This allows for great evil to be committed.

Doing evil requires modern infrastructure. It means people doing the office work of evil, the logistics, the memo writing, the planning meetings, the quarterly reviews. Arendt argues most of the people involved in, and necessary for, the doing of great evil are separated from the actual acts of evil: killing people, brutalising them, taking away their homes, forcing them into camps, committing mass exterminations. Most people involved in the process that leads to great evil might not think what they are doing is evil.

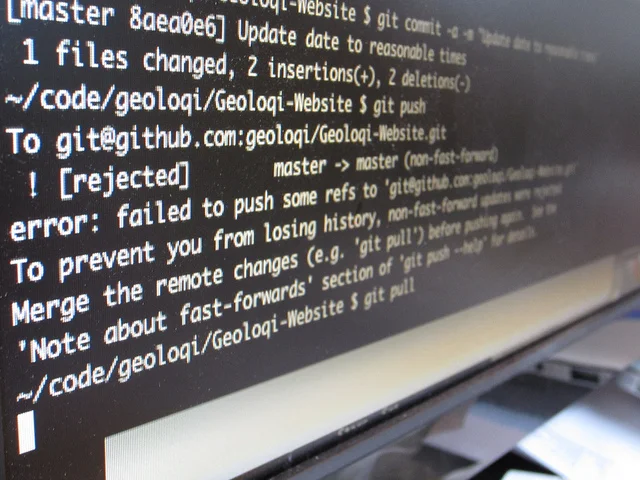

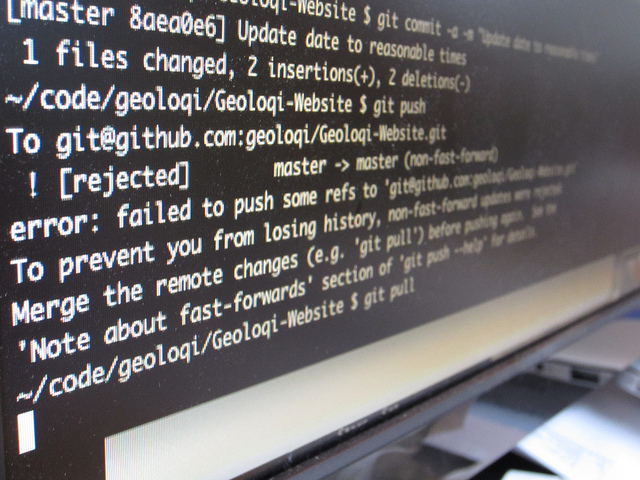

One of the biggest changes that has taken place between when Arendt was writing and today is that the kind of office work that Eichmann did has now been digitised. Computers have removed the need for a dystopian society to have legions of people typing out arrest warrants, a la Terry Gillingham’s Brazil. The growth of information technology means that you need fewer Eichmanns, people willing to do great evil but at a distance from it, to do something really terrible today.

Turning people into machines

As much as needing fewer bureaucrats is useful if you want to do evil, there is a more significant change that information technology has brought about that makes totalitarianism more likely. For evil to occur, something needs to happen to turn ordinary people into people like Eichmann. That something is a process that occurs in totalitarian societies, like the ones that Arendt spent her life studying.

Arendt argued that a totalitarian political system, like the one in Nazi Germany, turned people into machines and this allowed them to do the extraordinarily evil things that the regime required. She called this The Banality of Evil. Arendt argued that Eichmann stopped thinking and thus was able to be a part of a genocide. She said we need to watch out for anything or anyone who seeks to subvert our capacity for critical thinking and turn us into machines.

Totalitarian societies turn people into machines and they don’t need machines to do it. However, our modern machines make it easier to turn people into the thoughtless drone that Eichmann became. To see why that is, we need to look at another work by Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism.

How social media isolates us

Social media isolates us from each other as relations through technology come to replace non-technology-based relations. James Williams explores this in his book Stand Out of Our Light: Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy, in which he discusses how social media and mobile technology change our behaviour. One of these changes is a process that Williams describes as interactions on social media replacing the things we are seeking to achieve by using social media. This means that over time our goals change to be what social media platforms want, instead of what we want.

We might join a social media platform, install it on our phone, take it everywhere with us and check it all day because we want to connect with friends and family, or network with colleagues, but social media platforms are incapable of measuring how many meaningful social interactions we have. What it can measure is our attention to the platform, likes, clicks, video watches, etc. and platforms attempt to monopolise our attention so they can sell adverts.

Eventually, the platforms train us to see a like or comment as a social interaction with a friend or family member when they’re not the same thing. The platforms change our behaviour so that we see what they want, our attention on the platform, as what we want, for meaningful social interactions with others. Williams calls this process tech obscuring our starlight or our guiding principles behind our actions.

Our starlight is obscured

As our starlight is obscured, interactions on technology platforms come to replace meaningful human interactions. This means we become more isolated from each other, which Arendt identified as a precursor to totalitarianism.

Totalitarianism requires people to be lonely in a mass society full of people who are disconnected from each other. When you are lonely in a mass society everyone constantly assumes the worst about each other and people stop trusting each other. This is further aided by social media showing the worst aspects of humanity, from online abuse to petty put-downs. When social media has replaced meaningful social interactions, it’s easy to stop trusting other people.

Arendt wrote that totalitarianism requires people to be isolated from each other, but also be able to connect to form mass movements like the Nazi Party or the Russian Communist Party. Being lonely in a mass society is, ironically, a shared experience. Recruits to the totalitarian movement are both lonely and connected via their loneliness. Social media provides the dual purpose of isolating us from each other by taking the place of human interactions, and by allowing members of a nascent totalitarian movement to connect.

Undermining objective truth

There are other ways that modern technology can aid totalitarian movements, which is that social media, and the filter bubbles they create, undermines our shared understanding of the truth.

Arendt wrote an essay called Truth and Politics, in which she argued that facts are fragile and that organised lying is a threat to facts. She said that we cannot allow those in power to undermine the belief in facts all together. Public institutions like libraries, universities, etc. keep records of facts that can be shared and help maintain the truth. Totalitarian movements seek to attack these institutions.

By now all this should be ringing alarm bells and reminding you of our post-truth social media world where Donald Trump and his supporters attack the idea of objective reality with “alternative facts”. Arendt would have recognised the attack on truth as that of an aspiring totalitarian.

How social media undermines truth

Social media filter bubbles mean people only interact with people who share the same values, which means that a lie that reflects those values can spread without ever being troubled by the truth. Especially if that truth conflicts with these values as it will never be shared into those social media communities, protected by filter bubbles.

Platforms like Facebook and Twitter either present all information as equally valid (regardless of its source or validity) or emphasise pieces of information, articles, opinions, posts, etc. based on how much interaction they have had (again regardless of how truthful or authoritative they are). There is no quality scoring based on how true or false information is. A complete lie that generates more interactions on the platforms - as emotionally charged lies are likely to do - will appear more prominently than a mundane fact.

Arendt argued that once the idea of objective truth breaks down, the world can be reshaped to what it needs to be. Anyone can become a criminal. It can be said that a fair election was actually rigged. Human life can be redefined as worthless. These are the tools that totalitarian movements use to turn people into machines. Events like the above made it possible for Eichmann to do terrible evil. Recent technological changes have only made this easier.

Attacks on authority

Adding to the problem is the totalitarian attack on authority. Totalitarians are a subspecies of authoritarians, but at the same time they erode the idea that authority can come from anywhere outside of their movement.

Arendt wrote an essay called What is Authority? In which she argued that we no longer respect authority and this causes problems as authority is necessary for society to function. Arendt says that authority is how we get things done without having to use reason or violence. Teachers and coaches have authority, which is why we obey them. Authority allows things to be done efficiently.

Totalitarians attack other sources of authority whilst making the real sources of authority within their movement opaque. Arendt describes this in detail in The Origins of Totalitarianism. This process keeps citizens in a perpetual state of uncertainty as to who exactly has authority over them and what their instructions are. This uncertainty over authority is the everyday experience of Totalitarianism.

Choose your own authority

One reason totalitarians do this is to remove our capacity for action. Without authority, we cannot act together. The primary motivation for following an instruction is not authority but fear of violence. Arendt says that violence is the opposite of authority. A constant fear of violence is also the everyday experience of life under totalitarianism. This was most memorably captured by George Orwell’s description of Room 101 in 1984.

Social media and modern technology platforms attack authority in the way that they present information, opinions, articles, etc. based on how much they have been interacted with, instead of based on the authority of the author. This is because they want to show you content to monopolise your attention and not authoritative content. This undermines the concept of authority.

Filter bubbles that undermine the concept of objective truth also attack authority. In a post-truth world, authority can be anything or anyone you want it to be. It could be Alex Jones or Trump or someone from your neighbourhood. Why not choose an authority that shares your values? If we all live in a bubble where authority is the people we agree with then our capacity for action is reduced.

The importance of action

The idea of action is central to Arendt’s thinking and it comes up in several of her works. Arendt wrote about the importance of the Viva Activa or active life in her book The Human Condition. She said life had three elements: labour, which is the biological stuff people need to live, work, which is making things like tools that help us survive, and action, which is the social element of human life. Arendt argues that action is essential to political life. Totalitarianism prevents action.

Totalitarianism attacks action in many ways, which is enabled by modern technology. We have seen how it attacks authority which makes action possible, but tech also makes us isolated from each other. Furthermore, it obscures the starlight of our values changing the action we want to take into one that isn’t meaningful for us but benefits the technology platforms. On top of this, it attacks the concept of a shared truth, which is necessary for shared action.

Arendt’s warning

Action is the essential element of our meaningful social and political interaction with other people. The idea undermines a lot of Arendt’s other writing. Without our ability to create action, we are prey to totalitarian movements. Without action, totalitarian movements can turn us into unthinking machines, capable of doing great evil like Eichmann.

Arendt described all this in an age before modern computers, technology platforms and social media. None of these processes that Arendt described are new in the Information Age, however, changes in information technology do make it more likely for the processes that Arendt described to arise.